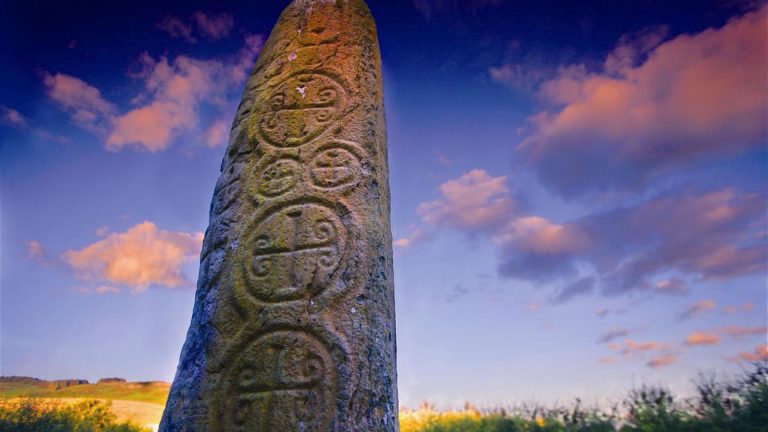

This captivating tale, drawn from the Irish folklore archives, echoes the symbolism and archetypes found in well-known stories like The Children of Lir, Snow White, and Little Red Riding Hood. Recorded in 1938, it weaves together familiar motifs such as the wicked stepmother, animal transformation, and magical restoration, hinting at a deeper, possibly pre-Celtic origin.

A Story of Universal Themes

The tale of The Princess and Her Brothers is classified in the ATU index of folktales as a narrative found across Europe. Its elements resonate with global mythologies, from the Greek figure Chione, linked to Snow White, to North African and Norse variants of Little Red Riding Hood. Similar versions appear in the works of Hans Christian Andersen and the Grimm Brothers, often featuring brothers transformed into swans or blackbirds.

What makes this Irish story unique is its potential shamanistic subtext, with themes of transformation and change that may reflect ancient spiritual beliefs. Could the twelve brothers even symbolize the divisions of the sky in a pre-Celtic Irish astrology? The possibility adds an intriguing layer to this archaic tale.

The Tale Unfolds

Long ago, a king and queen had twelve sons but longed for a daughter. One snowy morning, the queen gazed out her window, captivated by a scene: a calf’s blood stained the snow, and a raven perched nearby. She wished for a daughter with skin as white as snow, cheeks as red as blood, and hair as black as the raven’s feathers.

“When she saw them she wished she had a daughter with skin as white as the snow and cheeks as red as the blood and hair as black as the raven.”

(Irish Folklore Archives, Ref)

An old woman appeared, promising the queen a daughter but warning that her twelve sons would be taken away. The queen agreed, and when the daughter was born, her brothers vanished.

The Princess’s Quest

The princess, unaware of her brothers until she was twelve, became determined to find them. She set out on a journey and met an old woman who instructed her to make twelve shirts from bog-cotton, picked by her own hands, without speaking or crying. The princess began her silent task in a lonely garden.

Halfway through her work, a prince saw her and, struck by her noble bearing, proposed marriage. Despite his mother’s objections—claiming the princess was a mere woodcutter’s daughter—the prince married her, recognizing her true lineage.

After the marriage, twelve geese began appearing in the trees and flying over the house. When the princess bore a child, her jealous mother-in-law plotted against her. One day, while the princess slept, the mother-in-law gave the child to a wolf and smeared the princess’s mouth with blood, accusing her of eating her own child.

“One day she was out and she saw a wolf. She brought out the child and gave it to the wolf and smeared the mother’s mouth with blood so that they would think she ate the child.”

(Irish Folklore Archives, Ref)

The prince, deceived, ordered a fire to burn the princess. As she faced her fate, she finished the final shirt, with only half a sleeve left undone. At that moment, the twelve geese landed on a tree. The princess threw a shirt to each, transforming them into her twelve brothers—handsome men restored to human form.

Justice and Restoration

Breaking her silence, the princess proclaimed her innocence. The old woman who had cursed her brothers was revealed to be the wolf and the mother-in-law’s accomplice. The child was returned to its mother, and the cruel old woman was burned in the princess’s place. The prince and princess lived happily ever after, reunited with her brothers.

“The princess spoke and said she was innocent. The wolf was the woman she met the day she set out to seek her brothers… The young prince and his wife lived together happily ever afterwards.”

(Irish Folklore Archives, Ref)

Symbolism and Legacy

This tale brims with archetypal motifs: the wicked stepmother, the transformative power of animals, and the triumph of perseverance. Its parallels to Snow White, The Children of Lir, and other global myths suggest a shared storytelling heritage, possibly rooted in ancient spiritual traditions.

The twelve brothers, transformed into geese, may even hint at a celestial connection, perhaps reflecting an ancient Irish understanding of the cosmos. Whether a remnant of pre-Celtic astrology or a universal folktale, this story endures as a testament to the power of transformation and redemption.

For more on Ireland’s rich folklore traditions, explore Secret Ireland.

Author: David Halpin

Image: Three Swans in Flight by David Lloyd Evans

Source: Irish Folklore Archives