Listen up, you sons and daughters of the Emerald Isle, you Irish-American warriors with fire in your blood and a hunger for truth in your bones. This ain’t just a story about a man.

This is about Hugh Glass, a name carved into the wild heart of the American frontier, a name that echoes with the grit of a man who stared death in the face and spat in its eye.

Born to Scotch-Irish parents in Pennsylvania around 1783, Glass was no stranger to hardship, no stranger to the kind of raw, unyielding spirit that courses through the veins of those who carry the legacy of Ireland’s rebel heart.

This is the Hugh Glass true story, a tale of survival, betrayal, and a journey that makes the word “revenge” sound like a whisper in a storm. So grab a pint, settle in, and let’s tear into the legend of a man who crawled 200 miles through hell to prove he wasn’t done yet.

The Man, The Myth, The Irish-American Maverick

Hugh Glass wasn’t just a frontiersman; he was a force of nature, a fur trapper, hunter, and explorer with the soul of a poet and the fists of a bare-knuckle brawler.

Born to Irish immigrants who fled the old country for a shot at freedom in Pennsylvania, Glass carried the weight of his heritage like a badge of honor.

The Scotch-Irish, those fierce Ulster folk, didn’t just survive—they thrived in the face of adversity, and Glass was no exception. His early life is shrouded in mystery, but the whispers of his exploits paint a picture of a man who lived like he was running from the devil himself.

Captured by pirates under Jean Lafitte in 1816? Check. Forced to sail the high seas as a reluctant buccaneer? You bet. Escaping by swimming to shore near Galveston, Texas? That’s the kind of mad, defiant courage that screams Irish-American.

Rumors swirl that Glass lived among the Pawnee tribe for years, learning their ways, earning their respect, and maybe even finding a kind of peace before the frontier called him back. By 1821, he was in St. Louis, rubbing shoulders with Native American delegates and setting the stage for a life that would become legend.

This wasn’t just a man; this was a walking testament to the Irish-American spirit—unbreakable, unrelenting, and unafraid to take on the wilderness itself.

The Bear Attack That Shocked the World

Now, let’s get to the meat of it—the moment that made Hugh Glass a household name, the moment that inspired the Hugh Glass movie, The Revenant. It was 1823, and Glass was part of General William Henry Ashley’s fur-trading expedition, a ragtag crew of mountain men known as “Ashley’s Hundred.”

These were the kind of lads who’d make a Cork bar brawl look like a Sunday picnic. They were headed up the Missouri River, through what’s now Montana, the Dakotas, and Nebraska, when fate decided to throw Glass a curveball in the form of a grizzly bear.

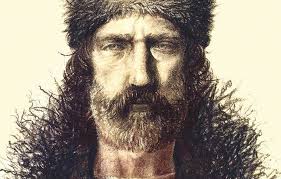

Picture this: Glass, scouting for game near the forks of the Grand River in present-day South Dakota, stumbles across a mother grizzly and her cubs. Why did the bear attack Hugh Glass? Simple—she was protecting her young, and Glass was in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The bear didn’t just attack; she tore into him like he was a rag doll. She picked him up, bit him, slashed him, and left him a bloody mess with a broken leg, gashes exposing his ribs, and a neck so torn it looked like his windpipe was breathing through the side.

His mates, hearing his screams, rushed in and killed the bear, but they looked at Glass and saw a dead man walking. Or rather, a dead man lying there, barely clinging to life.

How accurate is The Revenant bear scene? Let’s be real—The Revenant’s bear attack is a cinematic gut-punch, with Leonardo DiCaprio’s Glass getting tossed around like a leaf in a Galway gale. But the real story, while brutal, might’ve been less theatrical.

Accounts from the time, like those from trapper Hiram Allen, describe a savage mauling, but there’s no definitive record of Glass wrestling the bear like some Celtic warrior.

The film takes liberties, but it captures the raw terror and the sheer will to survive that defined Glass’s ordeal. Hollywood might’ve added some flair, but the core truth remains: Glass was a man who refused to die.

The Betrayal and the Crawl

Here’s where the story gets darker, where the Irish-American fire in Glass’s soul burned brightest. His companions, convinced he was a goner, decided carrying him would slow them down.

Ashley’s partner, Andrew Henry, asked for two volunteers to stay with Glass until he died and give him a proper burial. Enter John S. Fitzgerald and a young lad, possibly Jim Bridger (though historians still bicker over whether it was really him).

These two were supposed to be Glass’s guardians, but when they thought the Arikara were closing in, they panicked. They grabbed Glass’s rifle, knife, and gear, dug a shallow grave, and left him for dead. Hugh Glass Fitzgerald became a name synonymous with betrayal, a wound deeper than any bear claw.

But Glass? He wasn’t done. Not by a long shot. Alone, weaponless, with festering wounds and a broken leg, he woke up to find himself abandoned.

Most men would’ve given up, but not this Irish-American warrior. He set his own leg, wrapped himself in the bear hide his mates had left as a shroud, and began a 200-mile crawl to Fort Kiowa, a trading post on the Missouri River in present-day South Dakota. Where is Fort Kiowa?

It was a lifeline in the wilderness, a beacon of hope for a man who had nothing but his will to keep him going. Using Thunder Butte as a guide, Glass crawled, hobbled, and stumbled, surviving on berries, roots, and sheer stubbornness.

To fend off gangrene, he let maggots eat the dead flesh in his wounds—a gruesome but effective trick. Six weeks later, he staggered into Fort Kiowa, a living ghost with a story that would echo through the ages.

The Irish-American Quest for Revenge

Now, if you’re Irish-American, you know revenge isn’t just a word—it’s a fire in the gut, a promise to settle scores. Did Hugh Glass seek revenge? Damn right he did.

After recovering at Fort Kiowa, Glass set out to track down Fitzgerald and “Bridges.” He found the latter at a camp on the Bighorn River and, according to some accounts, forgave him, maybe because of his youth or maybe because Glass’s heart was bigger than his rage. But Fitzgerald? That was personal.

Glass tracked him to Fort Atkinson in present-day Nebraska, only to learn he’d joined the army. Killing a soldier meant a death sentence, so Glass settled for a warning: “Stay in the army, or I’ll find you.” The captain made Fitzgerald return Glass’s stolen rifle, and some say Glass got $300 as compensation—a fortune in those days, but nothing compared to the fire in his soul.

This is where the Irish-American spirit shines through. Glass didn’t just want blood; he wanted justice.

His journey wasn’t about killing; it was about proving he was alive, proving that no betrayal, no bear, no wilderness could break him. That’s the kind of defiance that runs through the veins of every Irish-American who’s ever faced the odds and said, “Not today.”

The Revenant: Hollywood vs. History

The Revenant, the Hugh Glass movie, is a masterpiece of grit and glory, with DiCaprio’s Glass dragging himself through a frozen hellscape to hunt down Fitzgerald. But how much of it is true?

Does Hugh Glass survive at the end of The Revenant?

In the film, yes, but it’s a brutal, ambiguous survival, leaving you wondering if he’s more ghost than man.

Why was Glass spared at the end of The Revenant?

The movie suggests a kind of spiritual redemption, a moment where Glass chooses life over vengeance, sparing Fitzgerald after a bloody showdown. In reality, Glass didn’t kill Fitzgerald, but not out of mercy—army rules tied his hands. The film weaves in a fictional Hugh Glass son, Hawk, to up the emotional stakes, but there’s no solid evidence Glass had a child. Sorry, folks, no Hugh Glass son in the historical record, just a lot of speculation and Hollywood magic.

The Hugh Glass true story is messier than the movie. First recorded in 1825 in The Port Folio, a Philadelphia journal, the tale was penned by James Hall, who might’ve spiced it up for drama.

There’s no direct writing from Glass himself to confirm every detail, and over the years, the story grew legs, tails, and maybe a few extra bear claws. But the core—the mauling, the betrayal, the crawl—holds up, backed by accounts like Glass’s letter to John S. Gardner’s parents, where he describes a deadly Arikara attack with the calm of a man who’s seen worse.

FAQs: Unraveling the Legend of Hugh Glass

What actually happened to Hugh Glass?

Hugh Glass was mauled by a grizzly bear in 1823 while scouting for Ashley’s expedition near the Grand River in South Dakota. Left for dead by companions John Fitzgerald and possibly Jim Bridger, he crawled 200 miles to Fort Kiowa, surviving on berries, roots, and sheer will. He later tracked down his betrayers but spared their lives, either out of necessity or forgiveness.

How long did Hugh Glass live after the bear attack?

Glass survived the 1823 bear attack and lived until early 1833, about a decade. He was killed by Arikara warriors on the Yellowstone River, alongside two fellow trappers, Edward Rose and Hilain Menard. His Hugh Glass cause of death was a violent end, fitting for a man who lived on the edge.

Did Hugh Glass have a child?

There’s no definitive evidence of a Hugh Glass son or any children. The Revenant’s portrayal of Glass with a son named Hawk is a fictional addition to heighten the drama. The real Glass’s personal life remains a mystery, with no records confirming a family.

Did Jim Bridger know Hugh Glass?

Possibly. The young man who stayed with Glass alongside Fitzgerald is often identified as Jim Bridger, a legendary mountain man. However, historians debate whether it was truly Bridger or another trapper named “Bridges.” If it was Bridger, Glass forgave him, likely due to his youth and inexperience.

Did Hugh Glass actually fight a bear?

Glass didn’t “fight” the bear in the Hollywood sense. He was attacked by a grizzly protecting her cubs, and the mauling left him near death. His companions killed the bear, but Glass’s survival was a battle against his injuries, not the animal itself.

Did Hugh Glass seek revenge?

Yes, Glass hunted down Fitzgerald and “Bridges” after his recovery. He forgave the younger man, possibly Bridger, and spared Fitzgerald because he was in the army, where killing him would’ve meant Glass’s own death. He got his rifle back and possibly $300, but his revenge was more about proving he was alive than spilling blood.

Does Hugh Glass survive at the end of The Revenant?

In The Revenant, Glass survives, but it’s a haunting, almost spectral survival. The film leaves him battered but alive, staring into the void. In reality, Glass lived for another decade after the bear attack, only to meet his end in 1833.

How did Hugh Glass stay alive?

Glass survived by setting his own broken leg, using a bear hide for warmth, and crawling 200 miles to Fort Kiowa. He ate berries, roots, and let maggots clean his wounds to prevent gangrene. His Irish-American tenacity and frontier know-how kept him going for six grueling weeks.

Why was Glass spared at the end of The Revenant?

In the film, Glass spares Fitzgerald after a brutal fight, influenced by a vision of his fictional wife and a moment of spiritual clarity. In reality, Glass didn’t spare Fitzgerald out of mercy but because killing a soldier would’ve cost him his life. The army captain ensured Fitzgerald returned Glass’s rifle.

How did Hugh Glass survive Reddit?

Reddit’s got no shortage of takes on Glass’s survival, with users marveling at his grit and debating the details. Some cite his use of maggots to clean wounds, others his navigation using Thunder Butte. The consensus? Glass was a badass, Irish-American or not, whose story defies belief.

The Later Years and a Tragic End

Glass didn’t retire to a quiet life after his ordeal. He returned to the frontier, trapping, trading, and hunting for the U.S. Army at Fort Union, North Dakota.

In 1833, the Arikara caught up with him on the Yellowstone River, and this time, there was no crawling away. Glass, along with Edward Rose and Hilain Menard, was killed in an attack.

His Hugh Glass cause of death was as wild as his life—a violent clash with the same tribe that had dogged him for years. A monument now stands near the site of his mauling, by Shadehill Reservoir in South Dakota, and the nearby Hugh Glass Lakeside Use Area is a testament to his enduring legend.

Hugh Glass height?

No records tell us, but you don’t need to be a giant to cast a shadow like his.

Hugh Glass real picture?

Sorry, folks, no photographs exist—cameras weren’t common in his day, but his story paints a vivid enough image. A man with the heart of a lion and the soul of a poet, forged in the crucible of the Irish-American experience.

The Irish-American Legacy of Hugh Glass

Hugh Glass wasn’t just a frontiersman; he was a symbol of the Irish-American spirit—fierce, stubborn, and unbreakable. His story, whether embellished or not, resonates with anyone who’s ever been knocked down and refused to stay there.

From the streets of Belfast to the pubs of Boston, the Irish-American community knows what it means to fight against the odds, to carry the weight of history and still stand tall. Glass’s crawl to Fort Kiowa wasn’t just a journey; it was a middle finger to fate, a testament to the kind of courage that runs deep in the blood of those who carry Ireland’s legacy across the Atlantic.

So raise a glass to Hugh Glass, you Irish-American rebels. His story isn’t just history—it’s a call to arms, a reminder that no bear, no betrayal, no wilderness can break a soul forged in fire. Whether you’re watching The Revenant or standing by his monument in South Dakota, remember this: Hugh Glass didn’t just survive. He lived. And he did it with the heart of an Irish-American warrior.