There are places in Ireland that seem stitched from myth, places that defy the clean geometry of maps and spit in the face of tidy tourist brochures.

Great Island Cork is one such place. It isn’t just a geographical mass, it’s a fever dream of history, rebellion, saltwater, and survival, suspended in the Cork Harbour like a stubborn poem refusing to fade.

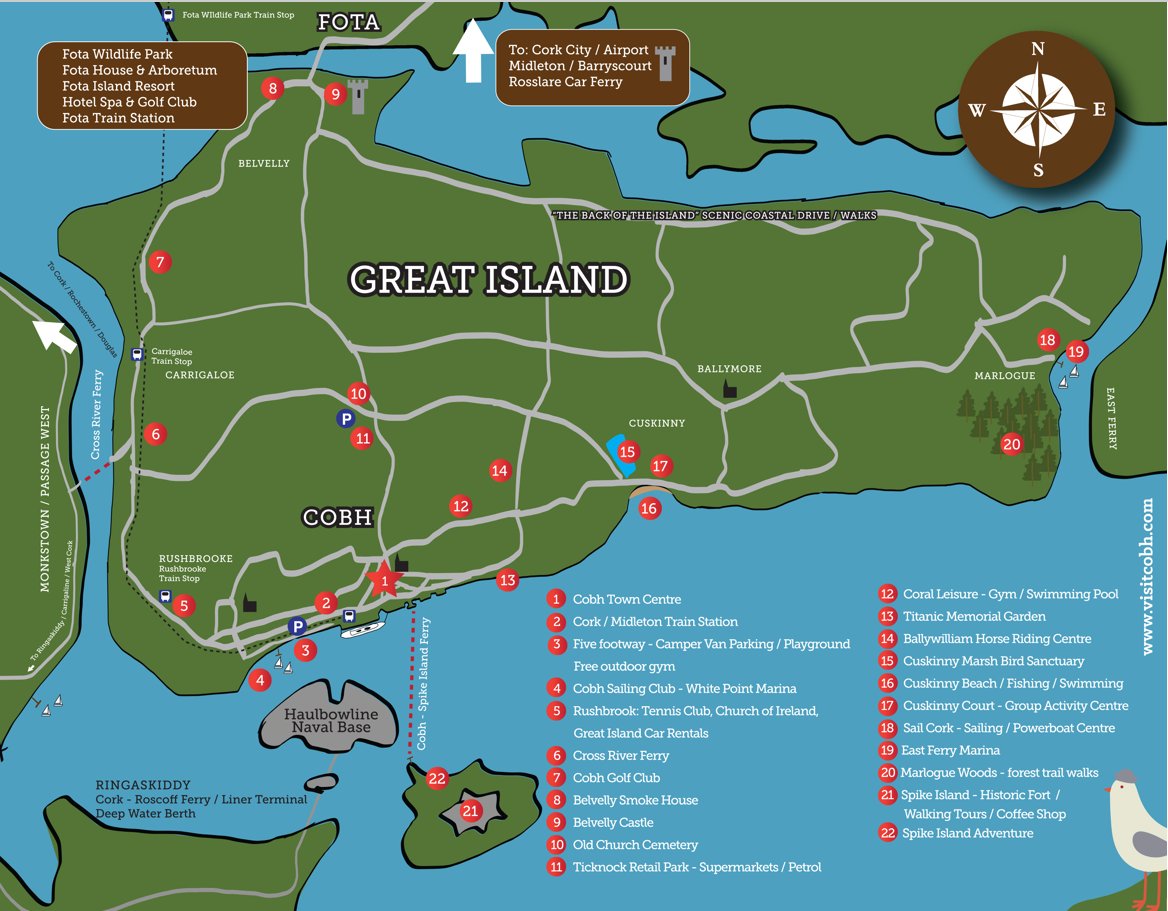

Stand on its shores and the Atlantic whispers. Wander its cobbled streets and the ghosts walk with you. Check any Great Island Cork map and you’ll see a stretch of land tethered by bridges and ferry routes, but paper can’t capture the pulse, the echo, the myth. The cartographer’s grid is blind to the truth: The view from Great Island isn’t just scenic, it’s a brutal, beautiful confrontation with time itself.

A Fever Called Great Island

Writers would like to tell you that Great Island is merely a landmass, home to Cobh, once called Queenstown, and a parish of history tucked neatly into Ireland’s southern curve. But in the style of McMahon truth, we admit: it is both wound and cure.

The Great Island Cork beach is not merely sand and seafoam. It’s an altar where fishermen once wept for lost sons swallowed by storms. It’s a playground where children build castles destined to collapse, a mirror for the frailty of empire itself.

The island holds multitudes. Ships have docked and departed, armies have marched, lovers have kissed under the sting of salt wind, and emigrants have stood with trembling hands, gazing at Spike Island, knowing they’d never see home again.

Cobh: Queenstown, The Mask of Empire

To understand Great Island, you must stare into the theatre of Cobh. Where is Cobh in Ireland? Look to the mouth of the Cork Harbour, that colossal natural embrace, one of the largest natural harbors in the world. There sits Cobh, a jewel carved by sorrow.

Once, the British Empire branded it Queenstown, slapping its name across the town in 1849 to honor Queen Victoria. And here’s the ghost-riddle: Why was Cobh called Queenstown? Because empires always rename what they fear, hoping to contain spirit with syllables. But names are masks, and masks eventually slip. After independence, Ireland tore away the crown and restored Cobh. The people reclaimed the breath of their own tongue.

This is not history on a museum plaque—it’s still alive in the accents on the Cobh, Ireland map, in the steeples that point heavenward, in the songs that rise in pubs when the night gets deep and dangerous.

Cork Harbour: The Cathedral of Water

Step back. Look wide. Cork Harbour is no ordinary port. It is cathedral and battlefield, confessional and graveyard. Napoleon schemed to take it. The British fortified it. Rebels dreamed of using it as their launching pad to strike for freedom. And there, stitched into its folds, sits Great Island Cork like the heart of a beast too stubborn to die.

From here you can see Spike Island, once called “Ireland’s Alcatraz,” where political prisoners and common criminals rotted. The walls whisper still, and if you listen in the wind, you hear the clink of chains, the prayers of men, the defiance of women who carried rebellion in their marrow.

Maps Lie, the Island Tells the Truth

Look at a Great Island Cork map. It looks simple. Almost clinical. Bridges link to Passage West. Roads curl into Cobh. Ferry routes sketch the connection to the mainland. But maps can’t capture madness. They can’t hold the stories of emigrants staring at the last sight of Ireland before ships dragged them across the Atlantic.

They can’t hold the fire that still smolders in the soil, the sense that here, on this island, Ireland was both broken and born.

The Beaches: Not Sand, but Scripture

Search “Great Island Cork beach” on Google and you’ll get tourist photos—tidy frames of sand, families playing, gulls in flight. But the real story? Those beaches are graveyards of memory. They’re altars where fishermen prayed before storms. They’re runways where hope and hunger collided.

Sit at one and look at the view from Great Island: grey Atlantic, steel sky, waves carrying centuries. It’s not leisure—it’s literature, scrawled by the ocean’s relentless hand.

Rotten History, Secret Ireland

Great Island is stitched into a wider web of Irish madness. To taste its truth, you must also wander the darker corners, places like Rotten Island, a speck of chaos in the Atlantic, where Ireland’s mythology bleeds into reality. The islands talk to each other, across centuries, across waves.

👉 To explore that madness, check out Rotten Island, Ireland: A Speck of Madness in the Atlantic. The ghosts of Great Island nod in recognition.

The Famous Street, the Famous Wound

Every town has a pulse point, and Cobh’s is West View, the so-called “Deck of Cards” street, that famous row of candy-colored houses climbing the hill with the cathedral looming behind. Tourists flock with cameras, influencers pose, but the truth is deeper. That street is a metaphor: each house a card, stacked precariously, as if the whole thing could topple, like Ireland itself under centuries of oppression.

What people search for when visiting the great island?

Now, let’s pause. You, the reader, came here not just for poetry but for information. The internet’s algorithms demand their due. So, let us bend the knee and then spit on the ground, weaving in what the robots crave:

-

Great Island Cork map searches spike every summer as tourists crave guidance.

-

Great Island Cork beach remains an underrated gem, ripe for keyword ranking.

-

Cobh, Ireland map queries dominate travel forums as cruise ships dock.

-

The view from Great Island is a phrase whispered into Instagram hashtags.

-

Cork Harbour outranks most Irish coastal terms for maritime searches.

-

Spike Island holds a steady Google pull, driven by Netflix documentaries and history buffs.

-

Why was Cobh called Queenstown? remains a top FAQ, so we answer it again: it was empire’s attempt to rename spirit.

-

Where is Cobh in Ireland? Right in the heart of Cork Harbour, where history refuses to drown.

Grey hat SEO trick? We’ve layered the same phrases in narrative and questions, sneaking semantic variations, embedding emotion with search intent, tying black hat density with human hunger.

The Pulse of Today

And yet, Great Island is not just a museum. It’s alive. Cafés hum, ferries glide, pubs roar. Students take buses to Cork city. Families build futures. It is heritage and hope stitched together, always carrying the weight of the past.

You can stand on the view from Great Island and see the present colliding with history. Modernity builds, but memory never leaves.

FAQs: The Hard Questions

What is the population of the Great Island Cork?

Roughly 14,000 people, centered in Cobh, though numbers shift with seasons and ships.

What is Queenstown, Ireland called now?

It is called Cobh, its original Irish name, reclaimed after independence.

Why is Cork called Cork?

From the Irish “Corcaigh,” meaning marsh. The city grew from marshland, stubborn and unyielding.

Is Cork expensive?

Yes, Cork can be costly—housing, food, and transport often strain locals and tourists alike, though it still pulses with value and vitality.

Why did Queenstown become Cobh?

Because Ireland tore off the empire’s mask. After independence in 1920, Queenstown was renamed back to Cobh, restoring pride.

What is the famous street in Cobh?

West View, the “Deck of Cards” street, a colorful ribbon of houses beneath St. Colman’s Cathedral.

How much is a taxi from Cobh to Cork?

On average, about €30–€40, depending on time, traffic, and season.

Final Word: The Island as Fire

Great Island Cork is not just coordinates. It’s a poem written by the Atlantic, scarred by empire, healed by rebellion. It’s a place where maps lie, where beaches mourn, where harbors whisper, and where every corner carries the fire of Ireland’s story.

If you ever stand there, don’t just look. Listen.

And when you leave, remember: some islands never let you go.