The Great Irish Famine (1845–1849)—also known as An Gorta Mór, or The Great Hunger—was not just a national tragedy; it was a turning point in Irish identity, history, and diaspora.

Triggered by potato blight and worsened by British government policy, it resulted in massive death, displacement, and emigration.

Let’s take a closer look at the Irish famine death toll, its causes, and long-term effects on Ireland and the world.

What Was the Irish Famine?

The Irish Famine began in 1845 when a fungus called Phytophthora infestans destroyed potato crops across the country. The potato was a staple food for millions, especially the rural poor, who had little access to alternative nutrition or income. Over the next four years, repeated crop failures, combined with economic and political inaction, created one of the deadliest famines in modern European history.

What Caused the Irish Potato Famine?

Though the blight sparked the famine, the real devastation came from structural inequality:

-

Overdependence on a single crop (potatoes)

-

British landlords controlling Irish land

-

Reluctance of the British government to intervene or halt food exports

-

Failure of relief efforts and public works programs

-

Evictions and the collapse of tenant farming systems

These compounded to turn a crop failure into a humanitarian catastrophe.

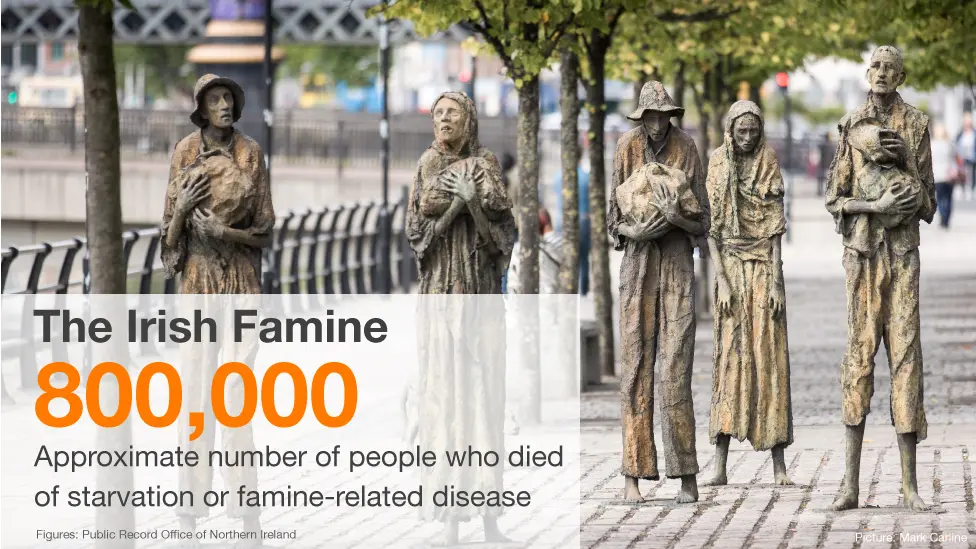

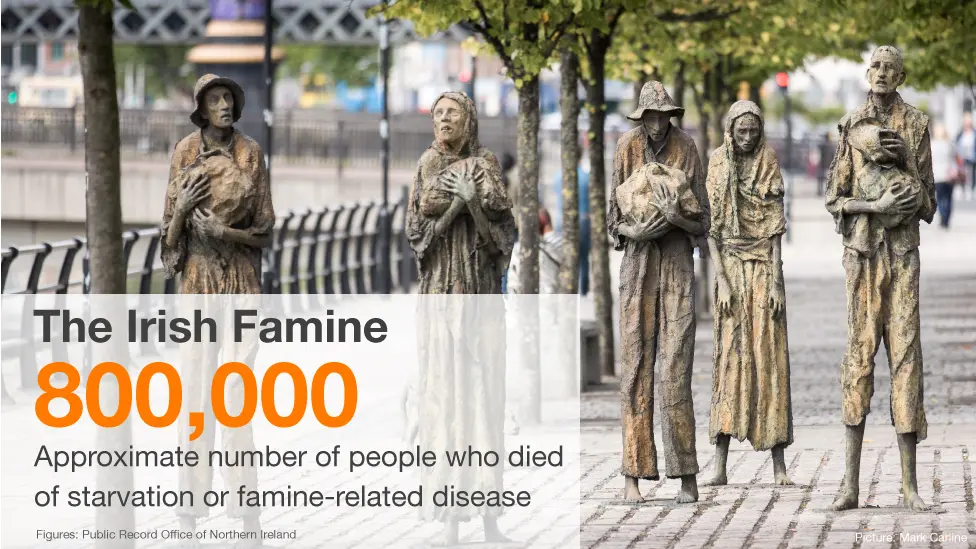

Irish Famine Death Toll: How Many Died?

Modern estimates put the death toll between 1 million and 1.5 million people. Many perished from starvation, but more died from diseases such as:

-

Typhus

-

Cholera

-

Dysentery

-

Tuberculosis

In some areas, entire villages were wiped out. The 1841 Irish population was around 8.2 million. By 1851, it had fallen to about 6.5 million. That figure includes both the dead and more than a million who emigrated, many on what became known as “coffin ships.”

Black ’47: The Worst Year of the Famine

The year 1847, known as Black ’47, was the most harrowing. Soup kitchens couldn’t keep up with the starving population. Public works schemes collapsed. People died by the roadsides. Mass graves were filled. And still, food exports continued.

What Ended the Irish Famine?

By 1850, the blight had begun to subside. But for many, it was too late. The population continued to fall due to emigration and a sharp decline in birth rates. The Irish agricultural system shifted dramatically in the famine’s aftermath, with tenant farming never fully recovering.

Long-Term Impact of the Famine

-

Ireland’s population has still not returned to pre-famine levels.

-

The famine fueled anti-British sentiment, leading to growing demands for independence.

-

It triggered a global Irish diaspora, particularly to the United States, Canada, and Australia.

-

The trauma lives on in Irish cultural memory, literature, and politics.

FAQs About the Irish Famine

How many Irish died during the Famine?

An estimated 1 to 1.5 million people died between 1845 and 1852 due to starvation and disease.

Why did the Irish rely so heavily on potatoes?

The rural poor depended on the potato because it was nutrient-dense, easy to grow on small plots, and often the only food they could afford. Other crops and livestock were typically sold to pay rent or exported.

Why didn’t the Irish eat fish or other food?

Many famine victims lived inland with no access to the sea. Even those near the coast lacked boats or equipment. The right to fish was often owned by landlords or the Crown. Infrastructure to distribute food was limited.

Who is to blame for the Irish famine?

The potato blight caused the crop failure, but British policy worsened the disaster. The government’s laissez-faire economic philosophy, reluctance to intervene, and continued food exports during the famine are widely criticized. Relief came late and was often poorly executed.

Why do the Irish blame the English for the Famine?

Because British authorities allowed food exports to continue, offered minimal aid, and enacted policies that many believed valued profit over people. There is ongoing debate over whether this constituted neglect or deliberate colonial cruelty.

What is a “coffin ship”?

“Coffin ships” were the overcrowded and disease-ridden vessels used by famine emigrants to cross the Atlantic. Thousands died en route to North America. In 1847 alone, over 5,000 Irish died at sea or in quarantine stations like Grosse Isle in Canada.

How many people emigrated during the famine?

Over 1 million people left Ireland during the famine years. Many fled to the United States, Canada, and Australia. Emigration remained high for decades afterward.

Was the famine a genocide?

Historians debate this. While the famine was not a genocide in the strict legal sense, many argue that British government inaction, apathy, and policies amounted to “soft genocide” by neglect. Others see it as a tragic consequence of colonial economics and bureaucracy.

Why was 1741 called “The Year of Slaughter”?

Over a century before the Great Hunger, a lesser-known famine in 1741 caused an estimated 300,000–480,000 deaths due to a combination of crop failure and epidemic disease. It was one of the deadliest years in Irish history until the 1840s.

What was the Catholic Church’s role during the famine?

Local priests and bishops often helped organize relief and soup kitchens. The famine also deepened Irish Catholic identity, especially as Protestant-run soup kitchens sometimes required conversion, a controversial practice dubbed “souperism.”

Is the film Black ’47 historically accurate?

Black ’47 (2018) is a fictional revenge drama set during the famine. While not a documentary, it realistically portrays the hunger, evictions, and brutality of the time and captures the desperation of Black ’47.

Final Thoughts

The Irish Famine death toll is more than just a number. It reflects a century of dispossession, misrule, and human suffering. The famine didn’t just reshape Ireland—it reshaped the world. It gave rise to the Irish diaspora, fed Irish nationalism, and left behind a legacy of grief, endurance, and remembrance that still lingers.

Understanding this tragedy isn’t just about history—it’s about justice, empathy, and never forgetting the human cost of political indifference.