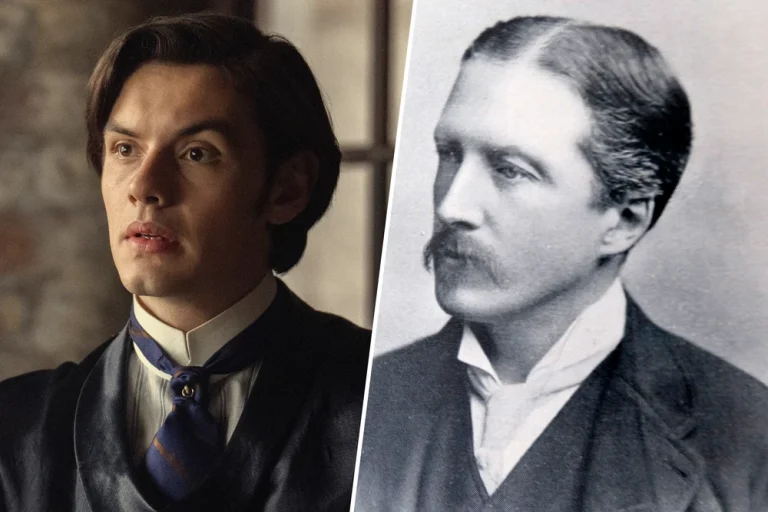

The tale of the Grapefruit Ladies Ireland ain’t no bedtime yarn spun from silk—it’s a thunderbolt hurled from the till of a Dublin shop, a sour citrus salvo that soured the sweet tooth of empire and apartheid alike.

Picture it: July 19, 1984, the air thick as porter in a Henry Street haze, and there stands Mary Manning, a slip of a girl at 21, eyes like embers in the Emerald Isle’s gloaming, refusing to ring up two measly grapefruits from the sun-baked hell of South Africa.

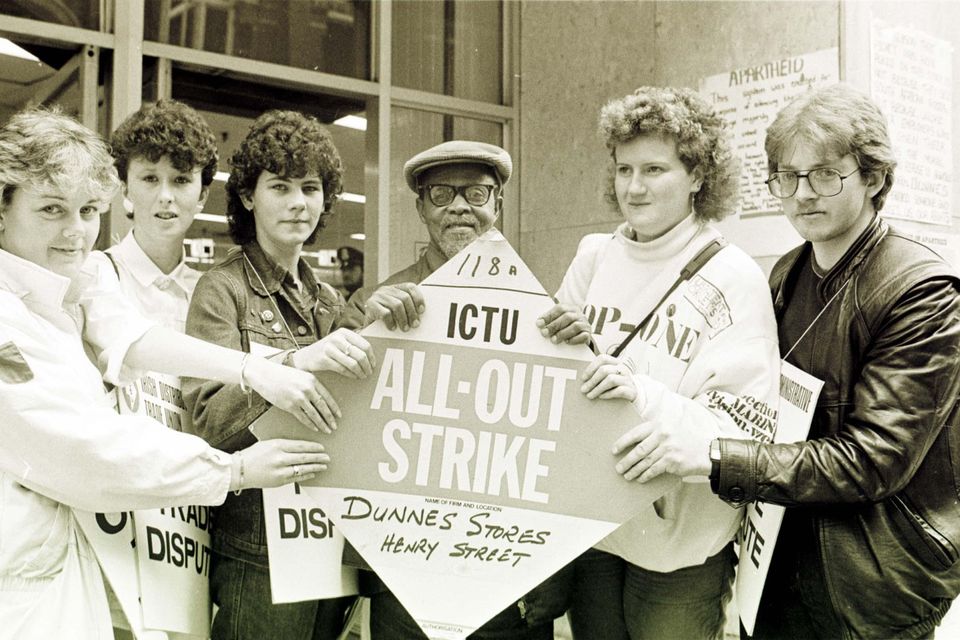

“No,” she says, voice steady as a shillelagh swing, “I won’t handle the fruits of their poisoned tree.” And with that? The fuse is lit, the picket line pitched, and eleven souls—mostly lasses with fire in their veins and fury in their fists—walk out of Dunnes Stores, sparking a strike that scorches the conscience of a nation and the globe beyond.

These Grapefruit Ladies Ireland, as the headlines howled and history hummed, weren’t born with banners in their prams—they were checkout clerks and shelf-stackers, young as the morning mist, scraping by on wages thinner than a famine farl.

But oh, the grit! Two years and nine months they held the line, rain-lashed and ragged, living on £21 a week strike pay, facing jeers from passersby and the cold shoulder from their own union brass.

What began as a union directive from IDATU—the Irish Distributive Administrative Trade Union—to boycott apartheid’s bounty became a moral maelstrom, a stand that shamed the suits in Leinster House and echoed to the ends of the earth.

By April 1987, Ireland—the first Western nation to do so—banned every last South African import, grapefruits ground to pulp under the boot of justice.

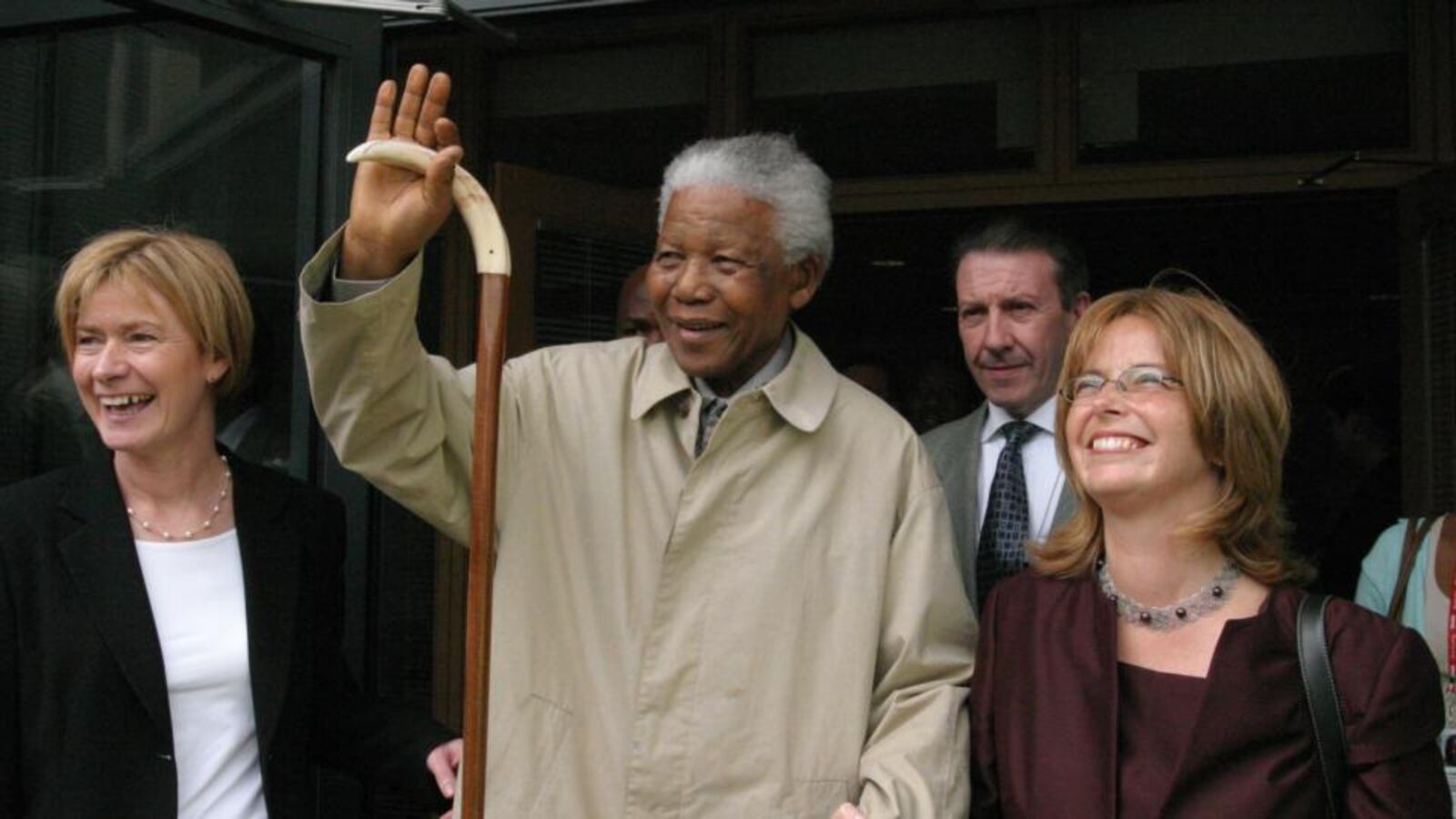

And Nelson Mandela?

From his Robben Island cage, where the sun baked his bones and the guards ground his spirit, he penned words that pierced like a pike: “Your stand kept me going,” he told them later, face to face in Dublin’s Freedom glow in 1990.

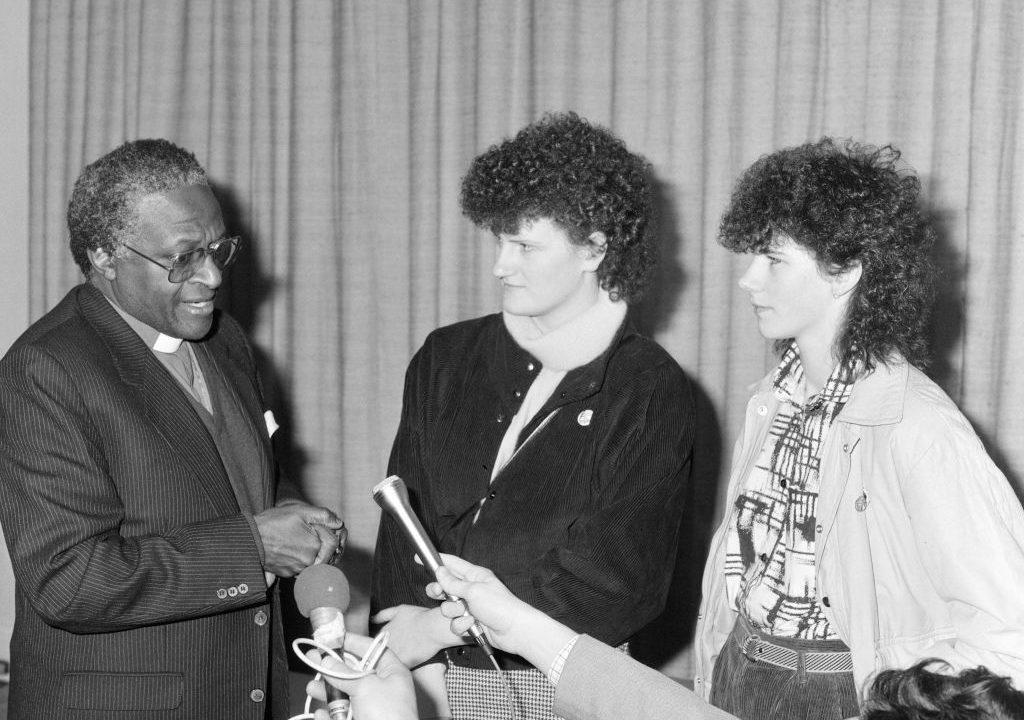

Desmond Tutu, that Nobel knight with a laugh like liberation, hailed them as heroes; the Catholic Church, once coy, climbed aboard the crusade.

Today, in 2025, as the world wrestles with its own weeds of injustice—Palestine’s plight, Gaza’s grief—the Grapefruit Ladies Ireland today stand as a snarling reminder: ordinary folk, armed with nothing but nerve and a notion of right, can topple tyrants taller than Table Mountain.

This blog? It’s their ballad, 2500 words of whiskey-warm witness to the Grapefruit ladies ireland history, the boycott that bit back, and the legacy that lingers like lime on the lip of change.

The Spark in the Supermarket: Birth of the Grapefruit Ladies Ireland History

Back in the boggy breath of the ’80s, Ireland was a land of leaden skies and lengthening dole queues, Thatcher’s chill wind whipping across the Irish Sea like a widow’s wail. Apartheid?

A far-off fever for most, a black-and-white blur on the telly between the news of hunger strikes in the North and Haughey’s handouts in the South.

But for Mary Manning and her mates—Karen Gearon, the shop steward with a spine of steel; Theresa Mooney, fresh from the ’83 national strike; and the nine others, lasses like Sandra Griffin and Michelle Gavin, all aged 17 to 24—they were just trying to keep the wolf from the door, tills ringing like reluctant rosaries.

IDATU’s directive dropped like a dud grenade in July ’84: no handling South African goods, a nod to the global growl against Pretoria’s poison.

Mary, at her post on Henry Street, faces the first test—a punter with two grapefruits, plump as privilege from the orchards of oppression. “I can’t,” she says, heart hammering like a hurley on the sliotar. Suspension follows swift as a Garda’s cuff, and out walk the eleven, pickets pitched outside Dunnes like a rebel camp in the Pale. Dunnes? They dig in, declaring no worker picks the produce— “We can’t let ’em decide what sells,” the bosses bark, blind to the moral minefield they’ve mined.

The early days? A dirge of disdain—abuse from shoppers spitting “Scab!” though they were the strikers; co-workers crossing the line like Judas at the last supper; even the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement’s Kader Asmal withdrawing support by October, calling it a sideshow to the main event.

Low points? Aye, plenty—Christmas ’84 with pockets picked clean, birthdays blown on strike-pay scraps. But the fire flickered: Nimrod Sejake, a South African exile, joins the line, his tales of township terror turning grapefruit guilt to granite resolve.

By December, Desmond Tutu touches down en route to Oslo’s Nobel, clasping hands on the picket: “You’ve lit a light in the darkness,” he beams, inviting them south. Eight go in ’85—deported at the border, headlines howling worldwide.

Gradually, the tide turns. Seán MacBride, Nobel laureate and IRA old hand, thunders praise: “In Ireland’s dismal din, this is our pride.” The UN calls in ’85, the strikers addressing the anti-apartheid committee, voices velvet over the void.

Songs swell—Christy Moore’s “Dunnes Stores,” a ballad of the brave; Latin Quarter’s album dedicated to the dozen. Plays and plaques follow: Tracy Ryan’s “Strike!” in 2023, a Johannesburg street named Mary Manning Way.

The Grapefruit ladies ireland history? Not footnotes in famine’s fog—it’s the foreword to freedom, eleven everyday warriors wielding wallets as weapons against the world’s worst wrong.

The Picket Line’s Bitter Bite: Inside the Two-Year Siege of Solidarity

Two years and nine months—seven hundred-odd days of Dublin drizzle drumming on determination, the picket a ragged rosary of resolve outside Henry Street’s haunted doors.

Living on £21 weekly? That’s a farl and a fry-up if you’re frugal, a fistful of fags if you’re frayed. The lasses learned apartheid’s anatomy the hard way: Nimrod’s nightly yarns of pass laws and police batons, turning vague outrage to visceral vow. “It was the color,” Mary muses today, “ye can’t hide yer skin like yer creed— that’s what gutted us.”

Opposition? A gale-force gale—Gardaí hauling ’em for “obstruction” on the odd dawn, punters pelting produce past the line, Dunnes digging heels deeper than a ditch in the bog.

The union?

Tepid as tea left too long, other branches balking at the boycott’s bite. But breakthroughs bloomed: Labour Youth and Sinn Féin swell the ranks, dockers parade down the street in August ’84, boots booming like bass drums of defiance. The Catholic Church, once coy as a confessor, climbs aboard—bishops blessing the blockade by ’86.

Global gasps follow: BBC beams the boycott, The Guardian growls approval, the UN’s echo chamber amplifies the eleven’s anthem.

In ’86, the strikers suspend the siege when Garret FitzGerald’s government green-lights a ban probe— invoking ILO conventions on forced-labor fruits, Ireland edges toward embargo. April ’87: the ban bites, all South African spuds and steaks shunned till apartheid’s ash-heap. Victory? Aye, but pyrrhic—jobs lost, lines crossed, but legacies launched. The Dunnes Stores anti apartheid strike? A siege that starved the beast, eleven grapefruits grinding gears of genocide to a glorious halt.

High-Fliers in the Firestorm: The Irish Parachuting Team’s Apartheid Tumble

While the Grapefruit Ladies ground it out on Dublin’s damp pavements, another band of bold Irish souls soared into the storm— the national parachuting team, plummeting into Pretoria’s poisoned paradise for the 1983 World Championships.

High-fliers these—skydivers with hearts hurling toward heaven, jumping under azure African skies just as boycotts brewed like a banshee’s brew. South Africa?

A pariah by then, IOC ousting ’em in ’70, UN thundering sanctions since ’68, but the drop-zone dazzle tempted: world-class winds, world-record wings.

The team? A dozen daredevils, men and women with chutes packed tight as their principles—or lack thereof. They touch down amid the Veldt’s velvet vastness, medals minted in mid-air, but back home?

The backlash bites like a Boerboel. The Irish Aviation Council, scenting the stink of apartheid, yanks government grants for two years— “No funding for fascist frolics,” the decree damns. Banned from top meets for a twelvemonth, the sky squad grounded like geese in a gale.

Furore flares as the grapefruit fuse ignites: Garret FitzGerald’s government, gearing up to growl at Pretoria, catches the parachutists in the crossfire. “Traitors to the cause,” the tabloids thunder, anti-apartheid anthems anathematizing the aerial adventurers.

The team? Torn twixt triumph and tribulation— “We jumped for sport, not state,” they plead, but the plea falls flat as a failed freefall. Echoes of the Gleneagles Agreement, that ’77 Commonwealth pact pledging no play with Pretoria, ripple ‘cross the ranks: England cricketers exiled, All Blacks boycotted, but Ireland’s high-jumpers? A harsh homecoming, chutes stowed in shame.

Yet in the larger lament? A footnote to the fruit fight, a skyward sideshow underscoring the era’s ethical edge. The parachutists’ plunge?

A cautionary canter, reminding that even eagles can err when apartheid’s shadow looms long. As the Grapefruit Ladies picketed below, these high-fliers highlighted the heights to which solidarity soared—or plummeted—in Ireland’s anti-apartheid arc.

Mandela’s Muse: Global Groans and the Grapefruit Legacy

From Robben Island’s rock-quarried raggedness, Nelson Mandela marked the milestone:

“Your defiance demonstrated that ordinary people, far from the crucible of apartheid, cared for our freedom—and it kept me going through the long nights.”

Face to face in ’90, Freedom of Dublin in his fist, he clasps the eleven’s callused hands, tears tracing tracks down cheeks carved by chains. Tutu? Earlier encore, ’84 airport huddle: “You’ve hurled a harpoon into the heart of the beast.” Seán MacBride, Nobel kin to the cause, salutes: “Ireland’s lone light in the gloom.”

The ripple? Worldwide waves: Ireland’s ’87 import interdict inspires embargoes ‘cross Europe, echoing the UN’s ’85 sports sanction and the Commonwealth’s cultural clampdown.

Artists abjure Sun City—Elton and Queen croon elsewhere; athletes abstain, from All Blacks to Barcelona bids. The Dunnes dozen?

Dedications abound: Christy Moore’s mournful melody, Latin Quarter’s lyrical laurel, a 2014 doc “Blood Fruit” bleeding their bravery on screen. Plaques pepper Henry Street—2008’s Mbeki marker, 2015’s fuller flourish—while Johannesburg’s Mary Manning Way winds through the townships they touched.

Books bloom: Mary’s “Striking Back” with Sinéad O’Brien, a 2017 memoir mining the marrow of the matter. Plays pulse: Tracy Ryan’s “Strike!” staging the siege in Southwark’s spotlight.

And the parachutists’ parallel? A poignant postscript, their ’83 aerial audacity amplifying the ’84 groundswell, both bites at the apartheid apple. The Grapefruit ladies ireland history? A global growl, grapefruits as grapeshot in the guerrilla war on wrong, Mandela’s muse from the misty isle.

Grapefruit Ladies Ireland Today: Echoes in the Emerald and Beyond

Fast-forward to 2025, forty-one years on, and the Grapefruit Ladies Ireland today ain’t faded footnotes—they’re fiery fixtures, faces etched in eternity’s album, invited to Áras an Uachtaráin by President Michael D. Higgins on the 40th, his voice velvet with vindication: “You took the moral stand that shamed the world awake.” Mary’s memoir? A bestseller’s breath, her words a whip to the whip-scars of history.

Karen Gearon? Still a union lioness, roaring for rights in retail’s ragged ranks. Theresa Mooney? Teaching the tale to tots, turning grapefruit grudge to generational grit.

The group? Scattered but stitched—Sandra Griffin in social services, Michelle Gavin in the Garda, Alma Russell raising rebels of her own. Gatherings? Gala as a Galway hooley, anniversaries ablaze with anecdotes and accolades.

Higgins hails ’em as “touchstone of protest,” their stand a spark for today’s torches: Palestine’s plight, where BDS banners borrow the boycott blueprint, Gaza’s grief grinding global gears. “If we did it then,” Mary muses, “why not now?”—a query quaking the quiet of complicity.

Legacy’s loom? Wide as the wedge between worlds: schools scripting their saga, streets stenciled with their story, South Africa’s streets saluting their solidarity. The Grapefruit ladies ireland president? Not a title, but a nod—Higgins as honorary herald, or perhaps Mary Robinson’s reformist reign, first woman in the Park, her ’90s liberalization laced with the Ladies’ light. Today? They’re TED-talk titans, podcast pioneers, the pluck that proves: from a Dublin till to the throne of transformation, one grapefruit can gall the giants.

FAQs: Unpeeling the Grapefruit Ladies Ireland Enigma – Long Yarns from the Line

@davidnihill History meets comedy. Never judge a book by its cover 🙃 #history #storytelling #comedy #standup

What was the Dunnes Stores anti apartheid strike?

It kicks off on July 19, 1984, in the fluorescent flicker of Dunnes Stores on Henry Street, where Mary Manning, a 21-year-old till-tender with the fire of Fionn in her belly, stares down a shopper’s two South African grapefruits like they were grenades from Goliath’s garden.

“I can’t,” she declares, heeding IDATU’s directive to shun the fruits of forced labor, the poisoned produce propping Pretoria’s racial rot. Suspension slaps swift, and out pour the eleven—nine women, two men, aged 17 to 24, mostly fresh from the ’83 national strike fray—pickets unfurling like the tricolor in a Troubles gale.

The strike?

A snarl of solidarity, two years and nine months of pavement-pounding persistence, living on £21 weekly strike pay that barely bought a bacon rasher, let alone a ballad of bread. Dunnes?

Dug in like ditch-diggers, decrying worker whims on what sells—”We can’t let ’em cherry-pick the cherries,” the bosses bellow, blind to the moral magma bubbling beneath. Early echoes?

A dirge of derision—Gardaí hauling ’em for “hindering trade,” punters pelting past with produce in tow, co-workers crossing like Cain to Abel. Even IDATU wavers, the Irish Anti-Apartheid Movement’s Kader Asmal pulling plugs by October ’84, deeming it a distraction from the diplomatic dance.

But oh, the turnaround! Nimrod Sejake, a township exile with eyes like embers, joins the line, spinning yarns of passbook purgatory that peel back apartheid’s putrid peel. December ’84: Desmond Tutu, en route to Oslo’s Nobel, clasps hands on the hoarding:

“You’ve harpooned the heart of the hydra,” he hails, inviting eight south in ’85—deported at Jan Smuts, headlines howling ‘cross hemispheres. Seán MacBride thunders tribute: “Ireland’s lone lighthouse in the Leabharlann’s lament.” The UN summons in ’85, voices velvet over the void; Christy Moore croons their crusade in “Dunnes Stores,” a ditty that drips defiance.

By ’86, Garret FitzGerald’s Fine Gael probes the ban, invoking ILO edicts on enslaved spuds—April ’87 seals it: Ireland, first Western whip to the wire, wallops all South African imports till the regime’s rubble. Victory’s vindication?

Mandela’s missive from the Rock: “Your grit grounded me through the grind.” Face-to-face in ’90, Freedom of Dublin in fist, he folds ’em in embrace. Plaques pepper Henry Street—Mbeki’s 2008 marker, 2015’s fuller flourish; Johannesburg’s Mary Manning Way winds through the weeds they weeded.

The Dunnes Stores anti apartheid strike? Not a footnote in famine’s fog—it’s the foreword to freedom’s feast, eleven grapefruits grinding the gears of genocide to glorious grit, a Dublin defiance that dethroned distant despots.

The Last Lilt: Grapefruit Ladies Ireland – Sour Fruit, Sweet Solidarity

So raise a ragged rosary to the Grapefruit Ladies Ireland, those till-side titans who turned tart defiance into triumphant tide— from ’84’s grapefruit grudge to ’87’s global growl, their stand a snarl that starved apartheid’s belly. The Grapefruit ladies ireland history?

A howl from Henry Street that hallowed the humble, proving one refusal can ripple to Robben’s redemption. Today? They’re Áras-honored elders, Higgins’ heralds of hope, their legacy a lash against today’s tyrants—from Gaza’s grief to wherever wrong wears a white hood.

The parachutists’ plunge? A poignant parallel, high-fliers felled by the same fierce wind, underscoring the era’s ethical edge. In 2025, as the world wheezes under its own weeds, the Ladies’ lesson lingers: ordinary ire ignites extraordinary ire-land change. Sláinte to the sour spheres that sweetened solidarity—may their bite linger long, ye bold and the broken-hearted alike.