The Book of Durrow stands as a luminous beacon of Ireland’s Golden Age of monasticism, an era when Irish monasteries became centers of learning, artistry, and devotion. Created in the 7th century, this richly illuminated manuscript is among the oldest surviving examples of Insular art, predating the more famous Book of Kells.

The Book of Durrow is not merely a book; it is a testament to the synthesis of faith, culture, and artistic innovation that flourished in early medieval Ireland. In this blog, we’ll delve into the history, craftsmanship, and enduring legacy of this remarkable manuscript, exploring how it reflects the spiritual and cultural life of its time.

The Origins of the Book of Durrow

The Book of Durrow is thought to have been created between 650 and 700 CE, though its precise origins remain a subject of scholarly debate. Traditionally associated with the monastery at Durrow in County Offaly, the manuscript may have been produced there or at another major monastic center, such as Iona or Lindisfarne.

The monastery at Durrow, founded by Saint Columba (Colum Cille) in the 6th century, was a prominent center of learning and spirituality. As part of the Columban monastic network, Durrow played a vital role in the transmission of Christian teachings and the preservation of classical knowledge. The Book of Durrow exemplifies this mission, blending scripture with breathtaking artistic expression.

A Closer Look at the Manuscript

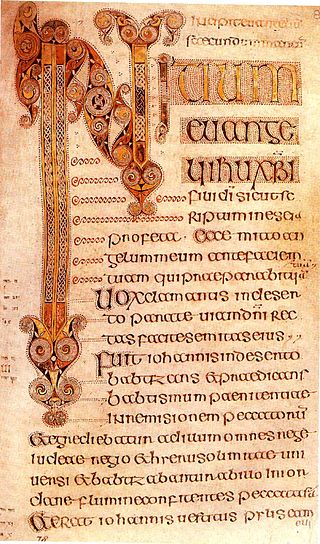

The Book of Durrow is a copy of the four Gospels, written in Latin and featuring elaborate illustrations that reflect a unique fusion of artistic influences.

1. The Text

The manuscript contains the texts of the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, along with prefatory material such as canon tables. Written in a crisp Insular majuscule script, the text showcases the meticulous craftsmanship of the monastic scribes.

2. The Illuminations

The Book of Durrow is renowned for its vibrant and intricate illuminations, which include full-page portraits of the four Evangelists, decorative initials, and ornamental carpet pages.

- Evangelist Symbols: Each Gospel is introduced by a portrait of its respective Evangelist, represented by a symbolic creature derived from the Book of Revelation: Matthew (a man), Mark (a lion), Luke (a calf), and John (an eagle). These figures are rendered in a highly stylized and abstract manner, embodying the spiritual essence of the Gospels.

- Carpet Pages: The manuscript features stunning carpet pages—full-page geometric designs that evoke the complexity of woven textiles. These pages demonstrate the scribe’s mastery of balance, symmetry, and color, creating a meditative visual experience.

- Initial Letters: The initial letters in the Book of Durrow are works of art in their own right, often enlarged and intricately decorated with spirals, interlace patterns, and zoomorphic motifs.

Artistic Influences and Innovation

The Book of Durrow reflects a remarkable convergence of artistic traditions, combining elements of Celtic, Anglo-Saxon, and Mediterranean art.

- Celtic Influence: The manuscript’s intricate interlace patterns and use of spirals are hallmarks of Celtic art, echoing designs found in stone carvings and metalwork from the period.

- Anglo-Saxon Influence: The geometric precision and linear motifs draw from Anglo-Saxon artistic traditions, likely influenced by contact between Irish and Northumbrian monastic communities.

- Mediterranean Influence: The layout of the text and the canon tables reflects the influence of late antique and Byzantine manuscript traditions, underscoring Ireland’s connections to the wider Christian world.

The Spiritual and Cultural Significance

The Book of Durrow was not merely a functional copy of the Gospels; it was a sacred object imbued with profound spiritual significance. Its creation would have been an act of devotion, intended to glorify God and inspire awe among those who beheld it.

A Tool for Worship

The manuscript likely played a central role in liturgical ceremonies, serving as a visual and textual focus for communal prayer and reflection. Its illuminations would have been viewed as a form of divine revelation, transforming the act of reading into a spiritual experience.

A Symbol of Authority

Manuscripts like the Book of Durrow also symbolized the authority and prestige of the monastic community that created them. They were treasured possessions, demonstrating the monastery’s commitment to preserving and spreading Christian teachings.

A Testament to Artistic Genius

The manuscript’s artistry reflects the innovative spirit of early medieval Irish monasteries, which transformed Christianity’s visual language into something uniquely their own. The Book of Durrow represents a pivotal moment in the development of Insular art, laying the groundwork for later masterpieces like the Book of Kells.

The Survival and Legacy of the Book of Durrow

The survival of the Book of Durrow is a testament to the care and reverence with which it was treated over the centuries. The manuscript is now housed in the Library of Trinity College Dublin, where it continues to captivate scholars and visitors from around the world.

Preservation Through Turmoil

During the turbulent medieval period, the Book of Durrow endured numerous challenges, including Viking raids and the dissolution of monasteries. Its preservation underscores the enduring value placed on such manuscripts as cultural and spiritual treasures.

A Source of Inspiration

The Book of Durrow continues to inspire artists, historians, and calligraphers, who marvel at its beauty and ingenuity. Its influence can be seen in contemporary Celtic art and design, which draw on the motifs and techniques perfected by its creators.

Visiting the Book of Durrow

For those eager to experience the Book of Durrow, a visit to Trinity College Dublin is a must. The manuscript is part of the college’s permanent collection, displayed alongside other priceless artifacts in the Long Room of the Old Library. The exhibition provides context for the Book of Durrow, situating it within the broader tradition of Irish manuscript illumination.

Why the Book of Durrow Matters

The Book of Durrow is more than a manuscript; it is a bridge to Ireland’s past, offering a window into the lives, beliefs, and artistic achievements of a vibrant and dynamic culture. Its pages tell a story not only of faith but of resilience, innovation, and the enduring power of beauty to inspire and uplift.

Discover More About Ireland’s Cultural Treasures

The Book of Durrow is just one of the countless marvels that make Ireland’s history so rich and compelling. To explore more about Ireland’s cultural heritage, from its ancient manuscripts to its monastic sites, visit Secret Ireland.

Dive into the stories, myths, and artifacts that define Ireland’s identity, and let your imagination take you on a journey through the Emerald Isle’s remarkable past.

There are not many people in the world who can say that they have performed in front of the Queen of England and there are even less people who can say that when they did perform in front of the Royalty they performed whilst being totally blind. But this is the case when its comes to a Monaghan Man called Patrick Byrne.

There are not many people in the world who can say that they have performed in front of the Queen of England and there are even less people who can say that when they did perform in front of the Royalty they performed whilst being totally blind. But this is the case when its comes to a Monaghan Man called Patrick Byrne.