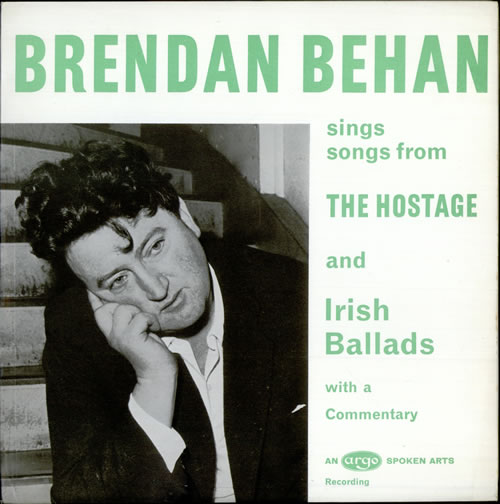

Ah, Dublin. A city steeped in more stories than a pint of plain. And among its most legendary yarn-spinners, its most audacious rebels, and its most heartbreakingly brilliant sons, stands Brendan Behan.

Now, if you’re expecting some dry, academic treatise, you’ve come to the wrong gaff. We’re talking about Behan, a man who lived life in technicolour, even when the world around him was stubbornly monochrome.

His legacy, you see, is as much wrapped up in the colossal, captivating persona he projected as it is in the unquestionable genius of his work. It’s a thorny bramble, this Behan business, and one worth untangling, even if it leaves a few scratches.

Born on February 9th, 1923, young Brendan popped into the world on Russell Street, smack bang in Dublin’s north inner city. He wasn’t destined for a quiet life, that much was clear from the off.

This was a lad who breathed the very air of rebellion and wit, soaking it up like a sponge. He soared to notoriety and global celebrity, not just because he could string a sentence together like a master weaver, but because he was, to put it mildly, an international cause célèbre. And therein lay the cruel irony, for that very celebrity, that insatiable hunger for the man behind the myth, inevitably forced Behan’s irreversible downfall.

So, how do we remember one of Dublin’s greatest, if not also most complex, literary figures? Can we peel back the layers of the boisterous public persona and truly appreciate the literary legacies of Behan’s unquestionable genius? It’s a task as challenging as trying to pour water uphill, but one we must attempt, for the sake of the man and his words.

Formative Years: Rebellion and the Pen

Young Behan, a bright spark indeed, was schooled by the good Sisters of Charity and the Christian Brothers on Dublin’s Northside during the roaring twenties and the grimmer thirties.

While learning the honest trade of a housepainter – a surprisingly grounding pursuit for a future literary giant – Behan found a different calling, a more fervent passion. In 1937, he joined the Irish Republican Army.

This wasn’t some casual dalliance; by 1939, he was arrested in Liverpool for IRA bomb activity, a young man already deep in the thick of it. He served time in a borstal institution in England, a formative experience that would later find its voice in one of his most celebrated works. He then did a stint in prison back in Ireland, hopping between Dublin and various colourful locations, including the bohemian streets of Paris, soaking up life in all its messy glory. In 1955, he married the wonderfully named Beatrice Ffrench-Salkeld, and they would welcome their daughter, Blanaid, in 1963.

His stories, raw and brimming with life, first saw the light of day in Dublin’s Envoy magazine, thanks to the discerning eye of John Ryan. His early forays into writing for the stage, even while incarcerated in Mountjoy prison in 1942/43, reveal a surprisingly disciplined and fastidious approach. The Landlady, a play depicting his own grandmother, was one such effort. Séamus De Búrca, clearly a man with a keen eye, offered Behan comments, prompting him to rework the play extensively. In a letter to De Burca in 1943, Behan, with his characteristic blend of humility and grandiosity, described the play as having “an old flush of Synge” in its language – high praise indeed. A manuscript of an Irish language translation, An Bean Ciosa, now resides proudly within the Abbey Theatre Digital Archive at University of Galway Library Archives, a testament to his early linguistic dexterity.

Behan’s literary ambition, coupled with that irresistible rogue-ish charm of his, led him to pen a cheeky letter to Ernest Blythe at the Abbey Theatre. He was enquiring about the Oireachtas competition for new novels. “I have no novel written,” Behan declared to the theatre’s then managing director, with a glint in his literary eye, “but for a hundred pounds I could translate Finnegan’s Wake into Irish.” Imagine the gall! Imagine the wit! This was Brendan Behan, in a nutshell.

The Ascent to Literary Stardom

His first major play, The Quare Fellow, premiered at Dublin’s Pike Theatre in 1954. It was a searing indictment of capital punishment, a play that depicted the unseen, condemned titular character, and served as a powerful critique of both the barbarity of the gallows and the burgeoning capitalist Irish society. Arthur Dreifuss later directed a film version of The Quare Fellow, shot evocatively at Dublin’s Kilmainham Gaol in 1961. Behan’s triumph here wasn’t about delivering a preachy lecture; it was about providing a point of profound political witnessing, allowing the audience to grapple with the injustice themselves.

Then came 1958, a watershed year. An Giall was performed at An Damer theatre in the city. Later, The Hostage, Behan’s English language adaptation of An Giall, exploded onto the international scene, achieving immense success following Joan Littlewood’s groundbreaking production in London in 1958. This play, a poignant tragedy about Leslie, a young English soldier held prisoner in a Dublin boarding house – a chaotic menagerie of sailors, whores, policemen, and the IRA – showcased Behan’s unparalleled ability to blend grim reality with a vibrant, almost carnivalesque theatricality.

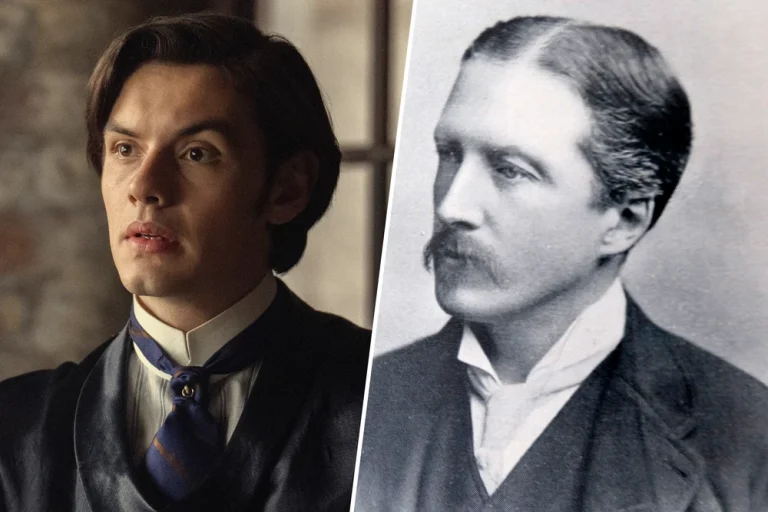

And if that wasn’t enough, 1958 also saw the publication of Borstal Boy, Behan’s autobiographical and deeply affecting novel. It was later adapted for the stage, directed by Tomás McAnna and starring the incomparable Niall Tóibín, opening at the Lyceum Theatre in New York in 1970, where it would deservedly win the Tony Award for Best Play. This work cemented his place not just as a playwright, but as a prose stylist of immense power. These Brendan Behan books are cornerstones of Irish literature.

In what was likely one of his last public interviews, speaking to RTÉ in early 1964, Behan, his voice slower, more considered, reflected on the recent abolition of capital punishment. “It is not my usual form to praise the Minister for Justice . . . but this recent move shows a good heart, an Irish heart. Nobody who was inside [in prison] before likes going to the gallows, saying those who swung often did so for an hour and if they were a Catholic, a priest would slit the hood and anoint them as they hung.” Even in his decline, his empathy shone through, his words carrying the weight of experience.

The Champions and the Censors

It’s crucial to acknowledge the powerful women who championed Behan’s early plays in the mid-1950s, both in Ireland and England.

From Carolyn Swift at Dublin’s Pike to Joan Littlewood at Stratford East, these visionary producers and directors were instrumental in bringing his work to life. Swift, in particular, meticulously edited the manuscript of The Quare Fellow, helping the play find its definitive form and ultimately convey the profound tragedy of Behan’s resounding criticism of capital punishment. Her husband, Alan Simpson, then directed the play at Pike. Littlewood, encountering him in London, described Behan as “very shy,” a fascinating counterpoint to his boisterous public image. Yet, his plays, shy or not, stirred powerful reactions from audiences, critics, and even authorities in both cities in the late 1950s.

It’s important to understand the context in which these Irish plays, like Behan’s The Hostage, or J.P. Donleavy’s The Ginger Man (1959), found their initial success. Both had their première productions in London before transferring to Dublin. Why? Because they were often seen as a direct challenge, a means of antagonising the formidable forces of censorship in Ireland, who deemed such works indecent, unsuitable, and frankly, dangerous for a conservative society.

Consider the fervent condemnation: Fr Gerard Nolan S.J. wrote to John Charles McQuaid, the formidable Archbishop of Dublin, in October 1960, practically quaking with trepidation. He was forewarning the Archbishop of the impending transfer of Behan’s The Hostage from London to Dublin’s Olympia Theatre. “The play is entirely unsuitable for the Dublin public, from every standpoint that matters. It is an utterly amoral piece, in part obscene, in context degenerate, and at times blasphemous and so totally devoid of any artistic value, as to be worthless. . . I have told [the directors of the Olympia Theatre] that even with cuts, the play can only soil their theatre and their own reputation for discretion and prudence in programming, and will probably result in considerable worries for the, at the civic level.”

Yet, notwithstanding such damning reports from the moral arbiters, the eminent theatre critic at The Sunday Times, Harold Hobson, famously declared The Hostage and The Ginger Man as being the “two modern plays in London through which blows the winds of genius.” Genius, indeed. And Behan’s genius was utterly undeniable.

The Downfall and the Legacy

The tragedy of his young, if not untimely, death was in both its grim predictability and its heartbreaking avoidability. Behan suffered immensely at the hands of his own celebrity and fame, a cruel paradox. This was coupled with his crippling addiction to alcohol, the insidious grip of diabetes, and a profound well of personal insecurities. He was, sadly, ably supported in his destructive drinking by a baying clique of followers and hangers-on, those who wanted a piece of the legend, oblivious or uncaring of the man beneath. Seán O’Casey, another titan of Irish letters, wrote to Behan’s brother, Dominic, in 1961, with a prescient and heartbreaking observation: “I amnt preaching when I say that the jolly lads who cheer Brendan on don’t give a damn about him, and he just hurts himself.”

Behan was trapped. He became a victim of the international success of his works, yes, but also of the very image of the Stage-Irishman made real – a heavy drinker, a captivating raconteur, but also a man suffering profoundly from chronic diabetes. Brief interventions of medical care towards the end, tragically, did little to stem the relentless march of Behan’s physical and creative decline. During one of his stays in a London nursing home in his later years, Behan penned a tender note to his “Darling Pet,” his wife, Beatrice Behan, stating: “I can write no more except to say I love you and hope to see you soon – Also I miss you. Mo grá thu” (My love to you). These Brendan Behan last words, or at least some of his last written sentiments, are a stark, heartbreaking contrast to the public persona.

Brendan Behan died in Dublin’s Meath Hospital on March 20th, 1964, aged just 41. His coffin, draped in the proud Irish tricolour, was carried through crowded Dublin streets, a final, solemn procession for one of its most colourful sons, to the Church of the Sacred Heart in Donnybrook before his burial in Glasnevin Cemetery. The city mourned. The world lost a truly unique voice.

Despite his relatively short life and those bursts of true literary ability, that astonishing wit, and that profound empathy, Behan left behind no small body of accomplished work. In Irish cultural history, 1964 is often associated with the breakthrough success of Brian Friel’s play, Philadelphia, Here I Come! But the greatest significance of all may be what was lost rather than gained in that pivotal year. One such loss was the death of playwright Seán O’Casey, a literary giant in his own right. But perhaps the greatest loss of all, the most poignant silence, was what remained unwritten, the uncreated masterpieces that died with Behan in March that year. His Brendan Behan poems and Brendan Behan songs, while not as voluminous as his plays and prose, reveal a lyrical sensitivity that hinted at even greater depths.

His legacy, therefore, is a tapestry woven with threads of brilliance, rebellion, joy, and profound sorrow. We remember the wit, the rebel, the playwright, the poet, the man who lived too fast and burned too brightly. We remember the Brendan Behan quotes that still sting with truth and humour, like these gems:

- “It’s not that the Irish are cynical. It’s rather that they have a wonderful lack of respect for everything and everybody.”

- “I am a drinker with writing problems.”

- “The most important things to do in the world are to get something to eat, something to drink, and somebody to love you.”

- “There is no such thing as bad publicity except your own obituary.”

- “The big difference between sex for money and sex for free is that sex for money usually costs a lot less.”

- “Other people have a nationality. The Irish and the Jews have a psychosis.”

- “I have never seen a situation so dismal that a policeman couldn’t make it worse.”

- “One drink is too many for me and a thousand not enough.”

- “New York is my Lourdes, where I go for spiritual refreshment … a place where you’re least likely to be bitten by a wild goat.”

- “What the hell difference does it make, left or right? There were good men lost on both sides.”

- “I am a daylight atheist.”

- “If it was raining soup, the Irish would go out with forks.”

- “Critics are like eunuchs in a harem; they know how it’s done, they’ve seen it done every day, but they’re unable to do it themselves.”

- “It is a good deed to forget a poor joke.”

And in remembering him, we are forced to confront the complex interplay between the artist and their art, the man and the myth. His life was a short, fiery comet across the Dublin sky, leaving a brilliant, indelible trail.

Brendan Behan: Frequently Asked Questions

What happened to Brendan Behan?

Brendan Behan died on March 20, 1964, at the age of 41, from complications arising from alcoholism and diabetes. His heavy drinking significantly contributed to his premature death. This is the Brendan Behan cause of death.

What was Brendan Behan’s famous quote?

While he had many famous quotes, one of his most widely recognized is: “It’s not that the Irish are cynical. It’s rather that they have a wonderful lack of respect for everything and everybody.”

Was Brendan Behan in the IRA?

Yes, Brendan Behan joined the IRA in 1937 and was actively involved. He was arrested for IRA bomb activity in Liverpool in 1939 and subsequently served time in a borstal institution in England and later in prison in Ireland.

What was Brendan Behan famous for?

Brendan Behan was famous for his talent and wit as a writer, particularly his plays and autobiographical novel. His most celebrated works include the plays The Quare Fellow and The Hostage, and his autobiographical novel Borstal Boy. He was also known for his larger-than-life public persona as a heavy-drinking raconteur and Irish rebel, often a subject of media attention, as seen in many news reports and the brendan behan – wikipedia entry.

Is Beatrice Behan still alive?

Beatrice Behan (née Ffrench-Salkeld), Brendan Behan’s wife, passed away in 1993.

What happened to Sheriff Behan in real life?

This question refers to Johnny Behan, a historical figure from the American Old West, specifically associated with the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral. He has no relation to Brendan Behan. Sheriff Behan continued his life in Arizona, holding various political and law enforcement positions, though his reputation remained controversial after the events in Tombstone.

Who was Brendan Behan’s wife?

Brendan Behan’s wife was Beatrice Behan (née Ffrench-Salkeld). They married in 1955.

Is Beatrice Woods still alive?

Beatrice Wood was an American artist, ceramist, and designer. She passed away in 1998 at the age of 105. She is not related to Brendan Behan or his family.

How many children did Kathleen Behan have?

Kathleen Behan (née Kearney), Brendan Behan’s mother, had nine children in total, though not all survived to adulthood. Brendan was the second of her children.