In his essay, Reconnecting To Everything, Professor Ronald Hutton argues that “…fairy narratives serve to re-enchant the natural world at a time of unprecedented ecological crisis.

They animate and personalise it, creating emotional links between practitioners and places, plants, and animals.”

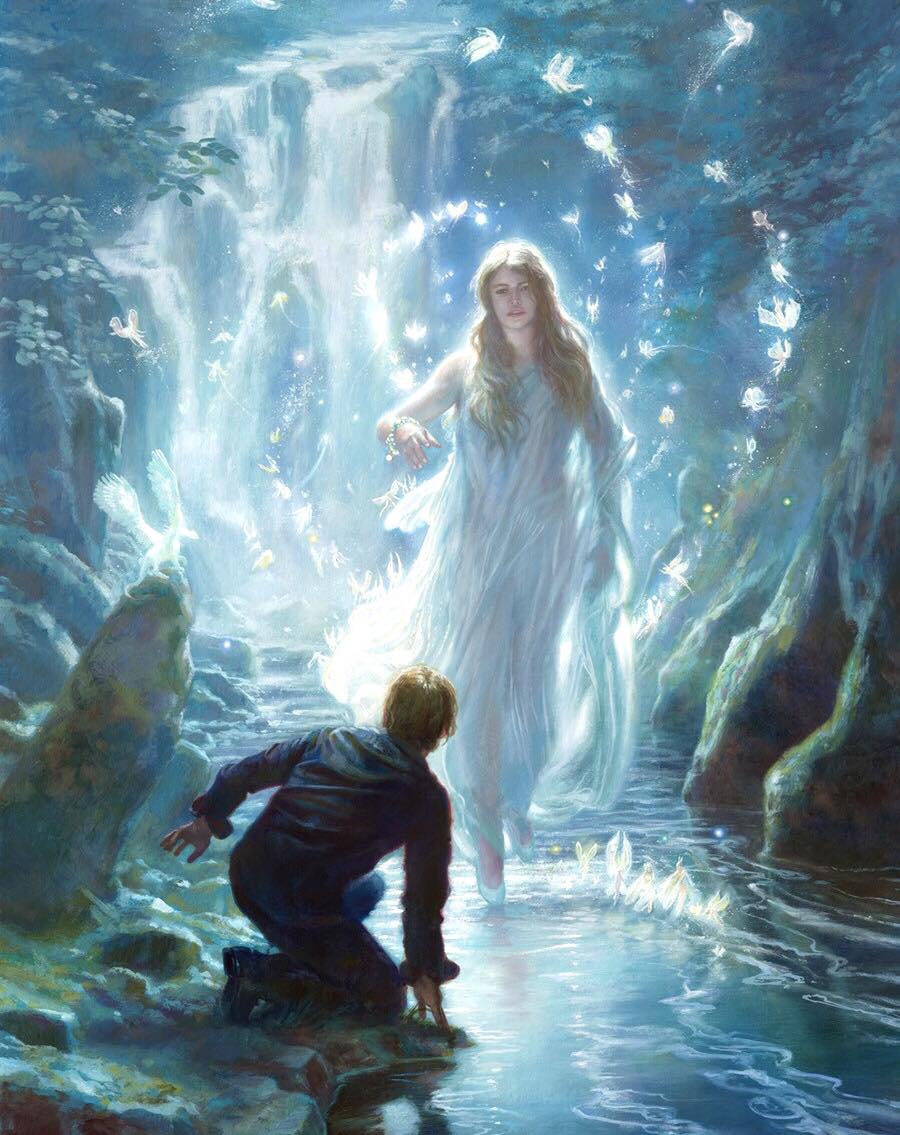

Professor Hutton goes on to state that re-enchantment requires imagination, and visualisation which stimulates the senses, moving us from disbelief to belief, making fairies and spirits real.

You might notice parallels to the concept of egregores to some degree here; thought forms created by the thinker and practitioner.

What is interesting, though, is how Professor Hutton also reminds us how such experiences are guided and constructed from our own preconceived ideas and imaginings: images of fairies from literature and film are waiting within the autonomous imagination for us to reuse over and over again.

We can also notice the recognition of how we are using fairies to populate new spiritual religions, which I have written about in previous posts, as well as the likelihood that we are framing ongoing and new experiences within the restriction of the beliefs of previous generations.

As an example, I was recently reading a collection of ‘ghost’ stories by the writer Robert Aickman and I couldn’t help but be struck by how many ‘ghosts’ actually seemed to behave more like fairies.

Indeed, even the strange phenomena that these beings brought with them belonged more to how we conceive of fairy experiences than anything else.

From time slips, to not accepting food or hospitality from such otherworldly or threshold beings, the dangers manifested the same way: being lost forever in a never ending loop, losing memory, becoming enslaved to a particular form, or even dying but remaining with the ‘ghost’, all seemed recognisable punishments or outcomes from fairy lore.

For some pagans, though, not moving from one particular way of thinking is of paramount importance, and a person must adhere to the rules of an exact ritualised liturgical slog.

For others, like myself, there is a feeling that rather than any one infallible ‘way’ there are myriad connections and a wild, chaotic, and localised, animism, which we are always connected to.

Our consciousness is awake to this numinous song to varying degrees, depending on circumstances, conscious clarity, and metabolic make-up.

This idea that a person must consciously reach out and imagine in order to experience the transcendent is often contradicted by fairy lore, though, it must be said.

From being carried away by a fairy wind, captured by hearing a fairy tune, or even accepting a gift from a stranger at a stone circle at dawn (!), folklore tells us that in many cases a fairy encounter is not something actively sought.

Indeed, in many shamanic traditions such as the Ulchi, as one example, a person may train for many years to become a healer or shaman only for the spirits to choose their brother, sister, or spouse.

Such accounts and traditions illustrate that while an argument may be made for beings to exist within imagination, they are also capable of traversing and crossing the boundaries of our limited conceptions of such realms, demonstrating both their liminal qualities, and, perhaps, more so, our own.

Or, perhaps the answer is more in line with what Gordon White reminds us about imagination, “It is not in you. You are in it.”

(C.) David Halpin.

Photos: Boleycarrigeen.

Castleruddery.

Haroldstown.